This blog post has been written by Kayleigh Heister, a conservation student at Cardiff University. Before returning to university, Kayleigh worked for the National Trust for Scotland. She first came to the UK to complete her master’s degree in Heritage Management at Queen Mary University of London. Her main area of interest is wall painting conservation, but she is gaining practical experience with a wide variety of materials.

This blog post is written on my work restoring and conserving an ancient Egyptian shabti figure, which is on loan to the Egypt Centre from Harrogate Museums. When HARGM11044 first came to the Conservation Lab at Cardiff University in September 2024, it was in ten pieces (fig. 1).

|

| Fig. 1: HARGM11044 before restoration |

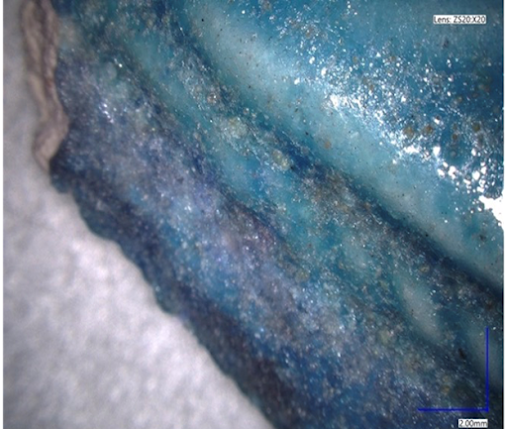

Aside from reassembling the shabti, the surface of the faience needed to be

cleaned and inspected for any salt degradation and potential future risks for

damage. The faience itself was cloudy in appearance, specifically the face as

well as other areas of the body. Faience commonly suffers from salt degradation

due to how they are produced with salt in the glaze and ceramic body. Therefore,

the cloudy appearance could be due to salt buildup (fig. 2).

|

| Fig. 2: Close-up of the glazed surface |

This necessitated further investigation using the

Keyence digital microscope, which provides a more magnified view of the

surface. Keyence revealed that it was not salt buildup, but rather a result of

the faience production. Dr. Ken Griffin informed me that the shabti dated to

the Ptolemaic Period (c. 305–30 BC). Shabtis during this period were

mass-produced, and the faience was made through the efflorescence method. This

means that the salts in the body would rise to the surface of the ceramic body

when fired to create the faience glaze. When it rose to the surface, bubbles

formed, and when the bubbles popped, it created a perfect little pocket that

minerals got stuck in (fig. 3).

|

| Fig. 3: Close-up of the surface showing bubbles. |

A surprise find was four areas of old adhesive stuck

to the ceramic body, though there are no records of a previous break or repair.

The old adhesive had begun to flake and was easily removed with a pair of

tweezers. The reason for removal was to ensure that the new adhesive had better

contact with the ceramic body.

|

| Fig. 4: Cleaning of the shabti surface |

The first step in the treatment plan was to clean the surface to determine if any minerals stuck in the faience or attached to the surface could be removed. Cleaning was done with a mixture of water and industrial methylated spirits. Some dirt was picked up on the swabs (fig. 4), and the appearance of the faience improved when wet (fig. 5). Once the surface was all cleaned, reassembly could begin.

|

| Fig. 5: Before and after photos of the head |

The surface of

the ceramic next to where the shabti broke was primed with 10% Paraloid B-72 to

ensure that the adhesive could properly adhere to the surface and not fail.

After the primer was set, 30% Paraloid B-72 was used for a majority of the

pieces due to how big the gaps were between the joins. Three smaller pieces

were reattached with 10% Paraloid B-72 due to how clean the joins fit together.

Once the piece was reassembled and photos were taken (fig. 6), Ken was able to

read the hieroglyphs, which was one of the goals of the conservation treatment.

The shabti belonged to an individual named Djedher. The bichrome colour of the

glaze, particularly for the wig, resembles the shabtis of Petosiris, which were

excavated at Abydos (North Cemeteries, Cemetery G, tomb G50). It is therefore

likely that the shabti of Djedher also originates from this site (Janes 2012, 454–57).

|

| Fig. 6: The restored shabti of Djedher |

Bibliography

De Regt, C. 2017. Conservation

issues related to Egyptian faience: a closer look at damaged shabti from the

Dutch National Museum of Antiquities. MPhil/MA thesis, University of

Amsterdam.

Florek, St. 2023. Egyptian

Faience. Available at: https://australian.museum/learn/cultures/international-collection/ancient-egyptian/egyptian-faience/.

[Accessed: 18 March 2025].

Janes, G. 2012. The shabti

collections 5: a selection from the Manchester Museum. Cheshire:

Olicar House.

National Trust. 2025. What is a

shabti? Available at: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/discover/history/art-collections/shabti-faqs.

[Accessed: 18 March 2025].

Nicholson, P. 1993. Egyptian

faience and glass. Princes Risborough: Shire.

Riccardelli, C. 2017. Egyptian faience:

technology and production. Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/egyptian-faience-technology-and-production.

[Accessed: 18 March 2025].

Smith, S. M. 1996. The manufacture

and conservation of Egyptian faience. ICOM Committee for Conservation 11th

Triennial Meeting. Edinburgh, 1–6 September 1996. London: James & James

(Science Publishers) Ltd.

TQ

ReplyDelete